Techniques and Strategies for Developing Braver Horses and Humans

Relationship Based Horsemanship

Horses are prey animals. They are naturally skeptical of their environments, and rightfully so. If they weren’t equipped to scan their environment for predators and predatory behaviors, it’s likely horses wouldn’t have survived as a species.

Some horses and humans are more vigilant, while others tend towards being more curious about their surroundings. Genetic labs now test for both curious and/or vigilant genes in horses, a tool that can make it easier to assess early on what a horse’s tendencies are.

Tendencies are not fate. A curious horse, treated poorly or exposed to repeated scary events can become very spooky. A vigilant horse, given successive, positive experiences, can learn to be very brave, regardless of what happens around them.

Since I start horses, it’s especially important to me that I help them learn to calm themselves when scary things show up. I do this first by exposing them to scary stuff when I’m not riding. Once I’m confident that they have the ability to relax under pressure, we move on to experiencing those same things with me in the saddle. Over time, my horses will be exposed to all kinds of physical, mental, and emotional pressures, so if I can teach them to handle pressure before I ride, training becomes safer and more productive.

Some of the things that can make horses spook are:

Something unexpectedly shows up (a person walking around a corner)

Objects rolling along the ground

Unfamiliar objects (this can be shaped rocks, tractors, flags, and horse-drawn carriages to name a very few)

Unfamiliar or loud sounds

Coats being removed, umbrellas opening, dogs running, open garbage cans, dressage rails, other horses, puddles. Yes, puddles. To a horse with a more 2-dimensional view of the world, that puddle can look like an abyss.

There’s hardly anything in the human world that a horse hasn’t spooked at. That means you can’t prepare for everything. But the more experiences a horse has in your presence that don’t end in death, the braver that horse will become and the more trust he will have that humans will keep him safe. The timeline on bravery is unique to every horse.

Some horses can be “bomb proof”, meaning that no matter what happens around them, they’ll stay calm. Other horses never get that far. No matter how many good experiences they have, some thresholds can never be breached. This can limit what you are able to do with them.

If you need a “brave no matter what” horse, then it’s critical that you find a horse that has been raised and trained to be brave. And you must take care that your horse has no reason to believe you will put them in danger. Because for horses, as with people, trust is hard-earned and easily lost.

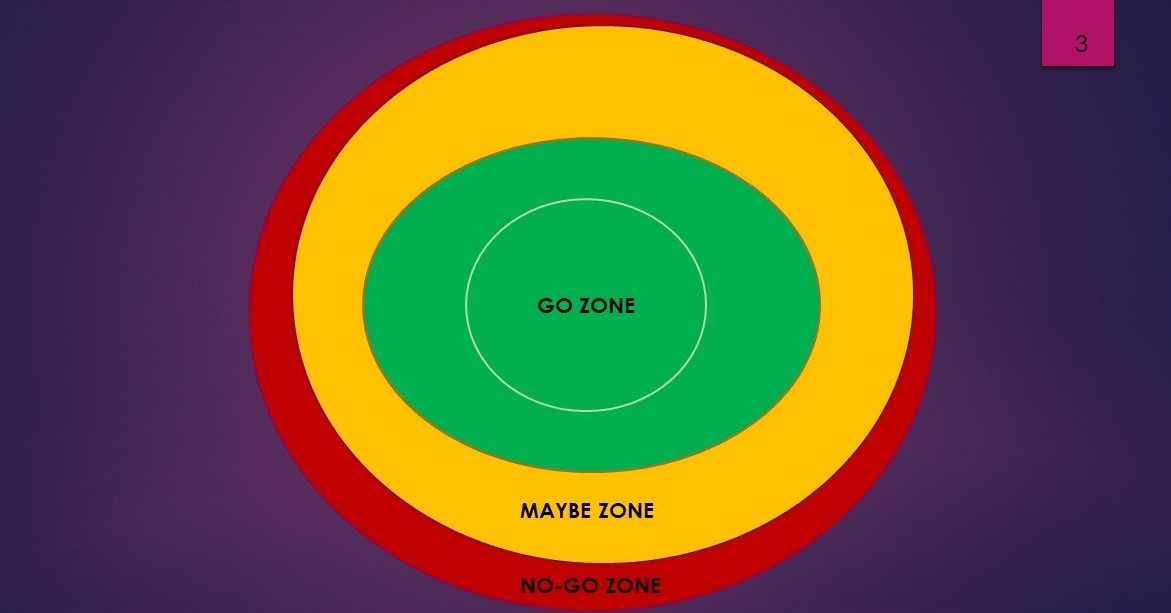

I go out of my way to figure out what bothers my young horses, then I lean into that hot spot with them. Here is a series of graphs that may help explain how I see the process. This view of how I expand comfort zones or GO ZONES, has been helpful in reminding me to approach my horse’s fear thresholds, then retreat back to where it feels safe until I can stay in the MAYBE ZONES longer and longer, eventually converting them to GO ZONES. If I push too hard and land in a NO-GO ZONE, I don’t stay there long. Neither my horse nor I am going to learn anything if we’re terrified.

It’s easy to forget that we have our thresholds of fear, too. The combination of a fearful horse and a fearful human can be a recipe for disaster. That’s where the saying, “Green (inexperienced) on green makes black and blue” comes from.

It’s a great idea to make a list of those things we fear along with those things our horse fears so we can work on those thresholds and minimize bruising experiences. Now mark those fears as MAYBE ZONE fears and NO-GO ZONE fears. Next, prioritize them and create a plan for dealing with those fear thresholds.

For instance, when mounting a horse, I insist that they stand absolutely still. I can identify what might spook a horse during mounting and then create a sequence for the mounting process that tests thresholds of fear along the way.

Jump up and down along each side of the horse until he can stand still with relaxation

Stand next to the horse and move the saddle side to side with vigor until they can stand still with relaxation

Put a foot in one stirrup and bounce on the other foot until they stand still with relaxation

Put a foot in one stirrup, bounce, then sit on one side of the saddle until they stand still with relaxation

Put a foot in one stirrup, bounce, sit on one side of the saddle, then smoothly and efficiently throw one leg over until I’m sitting on the horse, and they stand still with relaxation.

Once I’m seated, I teach the horse to bend his neck in both directions while standing still with relaxation.

With each step, I’m looking for a relaxed horse before I go to the next step. Many horsemen refer to these moments of relaxation as “green lights”. If the horse becomes tense or begins to move, I go back to the previous step. Horses live from moment to moment, so they can go from relaxed to tense very quickly. This demands that my attention doesn’t wander from what I’m doing. I have no problem repeating steps as much as needed to have a horse that learns to be obedient and stay relaxed. In the example above, once a horse learns this process, I can go through it in seconds. The steps become a “pre-flight” check of my horse’s state of mind. It gives me the “green lights” I need to feel comfortable about starting our riding session.

Eventually, I can stand next to my horse, hold a rein and my horse’s mane together, and press down into his neck as a prelude to mounting, and he will know he must stand still. Safety is built into the task.

It may seem obvious to state that it’s up to us to recognize and progress past our own fears, but many of the roadblocks to success can come from our own limitations. We can accept those limitations or work to improve them, but whatever they are, it’s important to recognize how they are impacting our horse goals and dreams.

It’s my responsibility to manage my thoughts and emotions, and to be physically capable of what I’m trying to do, all the while assessing my horse’s physical capabilities, mental readiness, and emotional stability. Which is why learning how to speak horse language is so important. How else could I figure these things out?

Sounds crazy complicated and difficult, doesn’t it? It is! That’s why horse training mastery takes years and years of study and practice. It’s also why dedicated horsemen of all levels love it so much.

Starting with some native talent doesn’t hurt, but talent can’t substitute for practice, discipline, and study. No matter where I am on the journey, there’s room to improve.

I also keep in mind that as I’m training a horse, I’m also the student of that horse, learning their strengths and weaknesses along with their personalities and how best to communicate with them.

There is nothing more fulfilling and exciting than improving upon then mastering a new skill or concept. I can’t do that without finding my own fear thresholds and pushing against them. Neither can my horse. It can be frustrating and a bit frightening at times, but it’s the only way to learn your limits and those of your horse.

It’s the easier path to fall into old patterns. This can happen by going too far into NO-GO ZONES, becoming terrified, and falling back to old GO ZONES.

Over-staying a NO-GO ZONE can result in never wanting to go there again. Touching and retreating from the NO-GO ZONES is how progress is made. Justifiable fears can be overcome this way.

We’ve all had the experience of overcoming fear and accomplishing a goal. Those are the experiences I must remember to help motivate me. Sometimes it’s helpful to make a list of desired positive outcomes that await the conquering of fear.

When I think about what might happen when I first ride a horse, fear is definitely in the mix. What I try to focus on is the preparation we’ve done together, the relationship we’ve attained, and the glorious rides that will come down the trail afterward. Our preparedness gives me the fortitude to push into my thresholds of fear. Green lights show me the way is clear.

It’s important to take time to access my horse and me as a team. Is any given problem mine or my horse’s or both? Understanding that we might both have thresholds in certain areas can create more reasonable expectations.

I must expect to progress if we are to succeed and manage expectations so I can make better decisions.

If we’re struggling, it’s likely I need to slow down and break tasks up into more bite-sized pieces, study more, and/or practice more. Successes can then build upon one another, leading to greater skill levels and confidence.

Slowing down can actually lead to faster, greater progress. Experimentation is allowed. Horses will forgive my mistakes if actions don’t come from meanness, anger, or frustration.

I see thresholds as question marks. Are we ready to proceed or not?

As obvious as this may seem, going there is the only way to get through to the other side.

For more information about the amazing horses that have been and are being bred on the HAAP farm, go to www.arabpinto.com

If you have questions for me about any of my posts, please feel free to contact me at isabellefarmer@gmail.com or visit our Facebook page at www.facebook.com/arabpintos